English Department

This user hasn't shared any biographical information

Buy or Borrow a Book this Summer!

The English Department would like to know what you read this Summer, so we have set you the following challenge:

The History Boys

“Pass the parcel. That’s sometimes all you can do. Take it, feel it and pass it on. Not for me, not for you, but for someone, somewhere, one day. Pass it on boys.”

This is some advice a teacher gives his students in “The History Boys”, and I believe, to some extent, this is the basis of all teaching. Teachers pass on what they know, and students then pass on their knowledge to another generation. You could say this is the basis of all civilisation. We learn from those who have gone before. We learn from our history. Or at least we should.

One of the things ‘The History Boys’ looks at is different teachers and their teaching styles. Should teachers focus on getting their students through exams to the exclusion of other learning? Or should teachers inspire their students well beyond the end of the year, to equip them with knowledge and culture that will go with them for the rest of their lives, long after the exams are forgotten. A gift that goes on giving. One boy, Posner, played by Ben, conveys this dilemma so well when he discusses his personal problems, “Literature is medicine, wisdom. Everything. It isn’t though, is it?”

The play is set in the early Eighties in a boys’ grammar school, where, after their A levels, the boys are taking exams to hopefully find places at Oxford. The last time I taught in England, in the early Eighties, I also taught in a boys’ grammar school and prepared students for a similar exam, though my boys were, I suppose, The English Boys. This was thirty years ago, and things have changed a great deal, and those times, Margaret Thatcher, the Miners’ Strike and music by New Order, are now part of history themselves.

To be able to stage “The History Boys” is a privilege, that we have the actors in school to be able to even cast it: a young teacher just out of college who looks like one of the boys (well, except for his beard), an older teacher on the verge of cracking up, a grumpy old headmaster, a good-looking boy who loves himself, a mild-mannered boy who knows everything there is to know about everything and a boy who plays the piano like ringing a bell. Sounds familiar? Actually, now I think about it, it was so easy to cast!

For me, one of the best things about the process has been working so closely with Bennett’s text. Bennett can make you laugh out loud and he can make you cry, but what makes him special is that he can do these two things sometimes in the same line: for example when Mrs. Lintott says, “What is history? History is women following behind with the bucket.”

Oh yes, and working with the actors, both teachers and students, has been sort of OK too. Love you dahlings, love your work!

John Grime

The History Boys will be performed in The Memorial Hall, Sunday 29th and Monday 30th June, 6:30pm. Tickets free.

NB: Some content may offend and is not suitable for students below Year 9.

Maya Angelou quotes: 15 of the best

With the death of Maya Angelou we lose the immense wisdom of the celebrated African American author, poet and civil activist. These quotes say a lot about who she was and what she stood for. Which other inspiring sayings would you like to share?

Never make someone a priority when all you are to them is an option.

If you don’t like something, change it. If you can’t change it, change your attitude. Don’t complain.

There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.

I do not trust people who don’t love themselves and yet tell me, ‘I love you.’ There is an African saying which is: Be careful when a naked person offers you a shirt.

We delight in the beauty of the butterfly, but rarely admit the changes it has gone through to achieve that beauty.

You may not control all the events that happen to you, but you can decide not to be reduced by them.

My mission in life is not merely to survive, but to thrive; and to do so with some passion, some compassion, some humor, and some style.

Try to be a rainbow in someone’s cloud.

I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.

I love to see a young girl go out and grab the world by the lapels. Life’s a bitch. You’ve got to go out and kick ass.

The love of the family, the love of the person can heal. It heals the scars left by a larger society. A massive, powerful society.

Courage is the most important of all the virtues because without courage, you can’t practice any other virtue consistently.

Nothing will work unless you do.

It’s one of the greatest gifts you can give yourself, to forgive. Forgive everybody.

I’ve learned that you can tell a lot about a person by the way (s)he handles these three things: a rainy day, lost luggage, and tangled Christmas tree lights.

William Shakespeare is the UK’s greatest cultural icon, according to the results of an international survey released to mark the 450th anniversary of his birth.

Five thousand young adults in India, Brazil, Germany, China and the USA were asked to name a person they associated with contemporary UK arts and culture.

Shakespeare was the most popular response, with an overall score of 14%.

The result emerged from a wider piece of research for the British Council.

The Queen and David Beckham came second and third respectively. Other popular responses included JK Rowling, Adele, The Beatles, Paul McCartney and Elton John.

Word cloud: a look at some of the names from the British Council research

Word cloud: a look at some of the names from the British Council researchShakespeare proved most popular in China where he was mentioned by 25% of respondents. The lowest score – 6% – was in the US.

Other events to mark Shakespeare’s birthday on Wednesday include a launch event for Shakespeare’s Globe theatre’s two-year world tour of Hamlet.

The tour aims to visit every country in the world. Venues will include Wittenberg in Germany, the Roman theatres of Philippopolis in Bulgaria and Heraclea in Macedonia, the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington and the Mayan ruins of Copan in Honduras.

The poet Michael Rosen wrote a celebratory poem for BBC Radio 4’s PM programme in which he picked out his favourite insults from Shakespeare’s works for use by people on social media.

It includes the lines:

“Thou cream faced loon

There’s no more faith in thee than in a stewed prune

Thou art baser than a cutpurse.”

A bugler plays a fanfare for Shakespeare in Stratford-upon-Avon

There will also be a firework display from the top of the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon after the evening performance of Henry IV Part I.

Shakespeare died on 23 April 1616 at the age of 52. His actual birth date in 1564 is unknown but it is traditionally celebrated on 23 April.

The British Council – which promotes British culture around the world – is planning a major international programme of events for 2016, the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death.

“The 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death is the biggest opportunity to put UK culture on the world stage since London 2012,” said Sir Martin Davidson, chief executive of the British Council.

“As the most widely read and studied author in the English language, Shakespeare provides an important connection to the UK for millions of people around the world, and the world will be looking to celebrate this anniversary with the UK. We hope that the UK’s cultural organisations will come together to meet these expectations and ensure that 2016 is our next Olympic moment.”

From The BBC

Shrewsbury International School’s entry into the 4th FOBISEA Short Story Competition 2014

Listen

By Miu Miu Chanya Leosivikul

“Do you believe in magic?” she asks, turning to me, her wide green eyes watching me intensely.

We were sitting on a grassy hill. The sky arched high above us. “Yeah.” I say, smiling. I thought she was just playing around when I turned to her, but she was dead serious. “Can you hear it then?”

“Hear what?”

“The magic, the songs.”

“What do you mean?”

“It’s hard to explain. I don’t know, just listen.” I strain my ears.

“I can’t hear anything,” I say. “What does it sound like?”

“It’s different, everything has its own song,”. I glance sideways to look at her, she was absently picking at the grass, her eyes bright, a faraway expression on her face.

She was a unique child. Clever, observant and wise beyond her years. I liked spending time with her.

“Like the wind, for example, it’s song can vary but today its lively and fun. It makes me want to dance.” she says, a smile in her voice. I didn’t really know what she was talking about. “And the trees,” she continues. “Their song is slower, starting low but getting higher. Like it’s growing taller. I like the sky’s song best. It’s clear and light. Makes me think of the clouds.” She was watching as the trees swayed side to side. Graceful dancers moving to a song I couldn’t hear.

I look at the sky, searching for clouds but there were none. The sky is the bluest I’ve ever seen. It’s endless. It is the perfect shade, not the washed out blue of winter or the crisp cerulean of autumn. But a clear blue with the slightest hint of turquoise. The kind of sky you only had in summer.

“What about the birds, up there?” I ask.

“Well, their song is quite energetic and fun. I know you’d love it,” She sighs, a frown tugging on her features. “I wish you could hear them too.”

She smiles sadly at me, the wind whipping her blonde hair around her small face. She seemed so innocent, so tiny, so vulnerable.

Maybe once, I had been able to hear those songs too. Children always seem to be able to see and hear things better than those of us who have grown up. I envy her. I wish I could still believe in magic. I had stopped believing a long, long time ago.

“Maybe I can sing something for you!” She says and her eyes seem to light up. She tilts her head back, the sun kisses her blonde hair. I watch curiously as she takes a deep breath. And then, and then, a sound graces my ears. She hums softly. No words, just sound flowing out of her. It sounds wistful and longing. She stops and says, “That’s your song.”

“Oh. Is that what I really sound like?”

“It depends. That’s what you sound like now but when you’re happy, it’s more lively.”

“Oh…” I wonder what her song sounds like.

“Shall I sing the wind’s song for you?”

“Okay.” She closes her eyes and the strange overwhelming sensation pours over me again as she hums. It sounds clear and pure. It might just be my imagination but the wind seems to grow stronger as she sings. I feel as if it could just lift me off the ground and just carry me away far, far away to some unknown place.

The melody is wild yet calm. I want to run a thousand miles. It’s beautiful.

I can imagine a whole orchestra accompanying her as she sings. All the animals coming out of the woods around to play for us. A trumpet, a harp, flutes and cellos. The drums, beating steadily, the violins sing. The notes flowing into the next, as bows danced over strings. The clash of a cymbal. The ring of a bell. The chimes, glittering in the background. The orchestra of nature.

All the different, beautiful sounds combining to be one. To be as one with the voice of the little girl. Her voice is enchanting. I feel as if the wind would whisk me up into the air, to the sky and we would soar over the treetops until the trees were ants and mountains were as small as the nail on your pinkie.

What I can see is only a small glimpse of the wind’s song. There’s so much more inside. So much beyond the music. It touches your emotions, it wakes you up, it triggers the old memories that you’ve long forgotten.

I could watch her sing forever, drowning all my fears, living in my dreams.

She stops abruptly and looks over at me worriedly. She’s afraid. Afraid of rejection. Her friends, her parents, not really ignoring her, but neglecting her all the same. No one understands her. I feel the pain she carries everyday because no one ever believes her. No one does, but I do. “I wish I could hear…” I whisper.

I thought she’d be upset but she grins at me instead. “Come on!” She says excitedly. “I’ll sing more, we can dance too! I can help you hear!” Maybe, maybe I could learn to believe again. Her smile is so wide and she looks at me like I’m her best friend not her babysitter.

She jumps up and grasps my hand. Soon we’re running together, hand in hand, down the hill. We tumble down to the bottom, laughing. She’s lying on the grass, giggling like mad and so am I. I close my eyes. Then, something melodic and quiet fills my ears. It’s her song. I open my eyes, a new wonderful world revealed before me and I could see it because I believed, because I believed in her.

Runner-Up

Molly 7SF

The Knife

Sokhem was ten when it happened. As was usual, he was making his way up to the hills to collect scrap metal to sell. The area was once a battlefield, so the treasure was ordnance left over from the Cambodian war. It sold for one dollar per 10 kilos. He had just arrived at a platform near the top when he heard the click.

Sokhem knew immediately that he was in trouble. He had seen and heard way too much to not know that there, at the bottom of his foot, lay a landmine.

He panicked on the inside and felt like screaming, yet he remained calm and still like a gravestone. He knew that if he moved there were two possibilities. He would either get blown to pieces, or at the very least lose his legs and bleed to death, alone, on the hilltop.

He scanned the platform. He felt sick to his stomach, and hopeless. He didn’t know that the situation was about to get worse, much worse. It begun when pain shot through his right leg and cramp set in. He felt strangely nauseous as he struggled to stay still.

He thought long and hard, as he forced himself to stop shaking. Tears slid down Sokhem’s face, and he couldn’t brush them off; just as he couldn’t slap the mosquito now sucking blood from his neck. Thoughts of his flesh and bone being torn to bits entered his mind. He knew death well, like an old foe, as he had lost his father and two brothers to that miserable war. Looking into the sky he then decided there was no point in waiting any longer to make his move.

He had heard from some of the older boys in the village that if you wedged an object tightly between your foot with some brands of mine, and no one he knew could verify this, it could lock the mechanism for a few seconds, and you had a chance.

In his belt was a small knife, it had been his father’s before his death. It had a silver rim, and a fire-breathing dragon had been carved into it. When his father had died, this had been the only thing that remained in the crater. Ever since, Sokhem has kept it with him night and day.

He pulled it from his belt and ever so slowly bent down. Carefully, he slid the blade under his shoe feeling the hard metal underneath. He felt around for what seemed like forever, sweat dripping down his face, stinging his eyes as the mosquitoes feasted.

click

He waited.

The blade had found its spot and stuck hard.

He closed his eyes, clenched his fists and took his foot off the device…

He opened his eyes, unsure if he was dreaming or not. Sokhem made a break for it, taking refuge behind some rocks on the ledge.

A loud bang followed rocking the ledge and the strong smell of sulfur filled Sokhem’s lungs. He looked around and walked toward where he had been standing only moments before. There, lying in the center of the ledge, in perfect condition, as if it had never moved, was his knife…

Runner-Up

Maomi 8PD

The Believer, the Skeptic and the Follower

“Hey, do you see that tree? The big bodhi one.”

The two men stopped and looked to the side of the trail they were walking on. The surroundings were very unruly, with leaves and twigs scattered all over the place. Robert glanced up at the huge tree that loomed over them. It had long thick branches that stretched out high above, each one adorned with brilliant green heart-shaped leaves. There were several cloths of different colours tied around the trunk of the tree, flapping eerily in the wind.

“Yes. What about it?”

“You notice how there are lots of colourful cloths tied around the trunk? That’s because it’s considered a sacred tree. We Thai people are very superstitious, and we believe in spirits that reside in these trees.” Dang explained.

Robert shuddered. No wonder the bodhi had such a creepy sensation.

Dang paused for a moment. “Do you believe in the supernatural?” he asked.

Robert hesitated. “I’ve always been intrigued by the idea of it, but I have to say I’m quite sceptical about these things.” he decided.

Dang shrugged. “There are so many strange things in the world that the scientists are still yet to explain,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean they aren’t true. In fact, there was a very curious incident about this very tree that happened a few years ago.”

Robert was instantly interested. “Is that so? Please do tell me about it. I know very little about Thai culture.”

“It started when a man came to this exact spot to pray on this tree to get rich.” Dang said, gesturing to the place where they were standing.

“And did he get what he asked for?”

“Well, weeks passed, and still nothing happened. One night, he came back drunk and went over to the tree with an axe to cut it down.”

“But obviously he didn’t succeed.” Robert said.

“No and yes. While he was hacking at the trunk, a large branch fell from the tree and hit the man, crippling his hand, which was so badly mangled that it had to be amputated. This resulted in the man receiving a large sum of money from the insurance company, granting his wish.”

Dang paused, letting the story sink in.

“Excuse me,” said a voice at his shoulder. “What are you doing here in the middle of nowhere? This is a sacred tree, and you shouldn’t be snooping around.”

The two men turned around to see a man standing behind them. He appeared to have overheard their conversation.

“Oh, nothing,” Dang replied, seeming quite annoyed by the man eavesdropping on them. “This is a public path. We were just passing by. Why do you ask?”

“Just my curiosity,” the man said, shrugging. “I’m Pauno, by the way.” He extended out a hand, which Dang and Robert both shook. After the introductions were made, Pauno glanced behind him, and looked up at the tree warily.

“I don’t see many people around this area,” he said. “It’s isolated, and it’s risky. Only strange people come here. But I do know a few things about this place, and there’s something I would like to do here.”

“I see. What is it that you intend to do?” Dang inquired.

“It doesn’t matter,” said Pauno, waving off the question. “Just tell me; what do you think of the man in the story?”

“I think he was very foolish to come here in the first place,” Robert said. “Praying to a tree won’t help you get your wish. If you want something, you’ve got to work hard for it. And nothing comes without a price.”

Pauno looked at him levelly. “I take it that you are a non-believer, and I have no intention to convert people like you. It will just be a waste of time. But just because something has no logical explanation doesn’t mean it isn’t true. Remember that.”

There was a moment of silence. “You still haven’t told us why you are here yet,” Robert said finally, trying to divert the conversation away from him.

Pauno sighed. “Oh, very well. I came here because I wanted to see this tree again. I definitely believe it to have something paranormal, you know. I have to come and pay respect to the tree every once in a while, or I wouldn’t be able to sleep at night. If something terrible has happened here, then it is best to stay on the safe side.”

“Oh? And why do you think that?”

Pauno gazed at Robert for a while. Then, in answer to his question, he slowly lifted his wrist out of his pocket.

He had no hand.

Link to FUSION 2014 Photographs: Copy the link into your browser https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B-rM6NJVWAmUanpmT3RCWjhzdVE&usp=sharing

In Defence of the Humanities

According to a recent piece of research from New College of the Humanities, 60% of the UK’s leaders have humanities, arts or social science degrees. The STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, maths) account for only 15% of the sample. This might come as a bit of a surprise for some.

Somebody studying the politics or sociology of Britain might reasonably infer from government policy that only people with STEM degrees make a contribution to the prosperity of the nation.

Moreover the literature from academics in support of the humanities tends to reinforce that supposition. Supports tend to argue that the humanities are vital for society because successful societies need to understand their past, the history of ideas and their culture.

This is true, but it misses a key argument underpinning the value of the humanities, the fact that graduates of these disciplines do incredibly well professionally, including those who follow business careers. What’s more, this is a vital part of the argument in favour of continued support of these subjects.

The full Choose Humanities report can be found here, but the data is pretty clear. The study reviewed leaders across a broad range of fields in the UK, including FTSE 100 CEOs, MPs, vice chancellors of Russell Group universities, Magic Circle law firms, managers of creative businesses and so on. Dividing subject areas between STEM, humanities, arts, social sciences and vocational, leaders with degrees from the core humanities were the largest group. Even among FTSE 100 companies there are 34 CEOs with a humanities degree against 31 with a STEM degree.

If so many of the UK’s leaders have humanities degrees, is it possible to determine whether what they have studied contributes to their success?

A good starting point is the business lobbying organisation, CBI. The CBI says that what big business needs are graduates who can work in teams, who can problem solve and who are numerate. This may be the basis of the government’s preoccupation with STEM subjects and it is certainly true that any client would be concerned if their auditor could not add up.

However, these are the basic skills graduates must have. They can only take professionals so far up the ladder. They are not the capabilities that will generate ideas or create wealth and employment. Steve Jobs’ obsession was with calligraphy, not cash flow statements. The capabilities that the CBI talks about are the plumbing (without being dismissive – you wouldn’t want to live in a house without plumbing). The humanities provide a rich training in the skills underpinning leadership and innovation, regardless of whether that leader runs a government department, a school, a newspaper or a corporation.

To succeed in the humanities you need to build an argument and you need to be able to recognise the strengths and weaknesses of the contrary position. Moreover you need to be able to present your position in a compelling and charismatic manner (the tradition of 1:1 tutorials is fantastic training for this). Purely on a practical level, the weekly distillation of a huge amount of material is exactly the discipline required in many forms of work.

If you appreciate, for instance, Bleak House or Nostromo, you will appreciate the importance of human relationships and the fact that it is people, as well as organisations and how they are structured, that shape outcomes. Most importantly, however, at the centre of the humanities is an appreciation of ideas and the value of creativity.

If Britain is to have a future in the economic life of the planet, it is unlikely to be in low value manufacturing. We will stand or fall with our creative and information industries and where better to find the leaders of these industries than from graduates of economics, law, philosophy, English and history.

Matthew Batstone is a co-founder and director of New College of the Humanities.

In the 17 years I’ve spent writing about technology, I have had the good fortune to meet, interview and chat with hundreds of game designers from all over the world. I have visited studios throughout the US, in Russia, in Japan, in France, Denmark and, heck, even Britain. And although the cultural references can often be hugely diverse, there are certain books and movies that come up in conversation over and over again.

Here, then, are the 10 books that game designers and developers have cited to me most often as influences on their work. There is a lot of science fiction and fantasy, of course – these being the predominant genres in the realm of mainstream narrative gaming. In some ways the list could be seen as evidence of the industry’s cultural homogeneity – the way in which big franchises like Mass Effect, Elder Scrolls and Halo all draw from similar influences. I think they will certainly give you a better idea of the concepts and conventions driving the games industry – perhaps they will tell you why we have the games we have. I should stress, however, that these aren’t the only books ever referenced to me in development studios.

Indeed there are no doubt ridiculous omissions – it was never going to be possible to capture all facets of game design inspiration. Also, I chose to stick with fiction to narrow things down a little. I’d invite readers to add their own suggestions in the comments section.

For now, here are the 10 books that developers from Osaka to Ohio have most commonly referenced to me. Each entry also has a few alternate titles (all of them also mentioned by developers) which I’ve sneakily added so fewer people would shout at me.

Whatever else, all of these are worth reading.

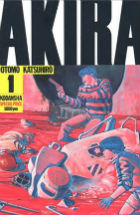

Otomo’s arresting and vivid portrayal of gang warfare on the streets of a post-apocalyptic Tokyo ran throughout the ’80s, drawing in influences from both the West (Star Wars) and the East (Japanese author Seishi Yokomizo), to dazzling effect. Widely credited with introducing both manga, and though its animated movie translation, anime, to Western audiences, Akira explores ideas of mutation, psychokinesis, military corruption and terrorism, all the while exhibiting the nuclear paranoia that flooded Japanese culture after 1945. Every Armageddon-obsessed adventure from Final Fantasy to Infamous has ideas that can be traced back here. Alternatively: Another classic 80s manga, Fist of the North Star, has been influential. And from the west, Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and Alan Moore’s Watchmen are two works dealing in similar areas of warped heroism, mutated humanity and future-noir paranoia.

Otomo’s arresting and vivid portrayal of gang warfare on the streets of a post-apocalyptic Tokyo ran throughout the ’80s, drawing in influences from both the West (Star Wars) and the East (Japanese author Seishi Yokomizo), to dazzling effect. Widely credited with introducing both manga, and though its animated movie translation, anime, to Western audiences, Akira explores ideas of mutation, psychokinesis, military corruption and terrorism, all the while exhibiting the nuclear paranoia that flooded Japanese culture after 1945. Every Armageddon-obsessed adventure from Final Fantasy to Infamous has ideas that can be traced back here. Alternatively: Another classic 80s manga, Fist of the North Star, has been influential. And from the west, Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and Alan Moore’s Watchmen are two works dealing in similar areas of warped heroism, mutated humanity and future-noir paranoia.

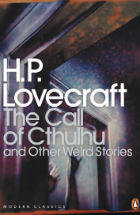

Through a selection of interconnected stories written throughout the twenties and thirties, American writer HP Lovecraft created a new horror mythology, blending the supernatural and science fiction and imagining a universe of dank oppressive dread in which humanity is at the mercy of gigantically powerful monsters. Lovecraft’s bestiary was a huge influence on the makers of seminal tabletop role-playing game, Dungeons and Dragons, thereby working its way into most video game RPGs ever since. And the Cthulhu Mythos that emerged from his works has had an enormous influence on games designers in other genres: indeed, the entire concept of ‘end of level bosses’ practically percolates Lovecraft’s entire philosophy into one game convention. Alternatively: other writers whose own complex fantasy/horror mythologies have inspired game designers include Michael Moorcock (especially the Elric books) and Stephen King (The Dark Tower). Lovecraft was also an influence on another provider of video game set texts, Robert Bloch.

Through a selection of interconnected stories written throughout the twenties and thirties, American writer HP Lovecraft created a new horror mythology, blending the supernatural and science fiction and imagining a universe of dank oppressive dread in which humanity is at the mercy of gigantically powerful monsters. Lovecraft’s bestiary was a huge influence on the makers of seminal tabletop role-playing game, Dungeons and Dragons, thereby working its way into most video game RPGs ever since. And the Cthulhu Mythos that emerged from his works has had an enormous influence on games designers in other genres: indeed, the entire concept of ‘end of level bosses’ practically percolates Lovecraft’s entire philosophy into one game convention. Alternatively: other writers whose own complex fantasy/horror mythologies have inspired game designers include Michael Moorcock (especially the Elric books) and Stephen King (The Dark Tower). Lovecraft was also an influence on another provider of video game set texts, Robert Bloch.

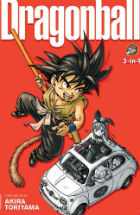

Originally serialised in the weekly Japanese comic, Shōnen Jump, Dragon Ball is widely considered to be one of the greatest mangas of all-time, its volumes selling over 230m copies worldwide. Based around the Chinese novel Journey to the West (the source for the cult TV series Monkey), the epic work combines exciting martial arts action and a Picaresque narrative heaving with eccentric and fascinating characters. There have been dozens of video game conversions of the original works, but Toriyama’s mix of combat, mythology and comedy has inspired hundreds more beat-’em-ups and action adventures. There are also dozens of games that make use of the “over 9000” meme, originating from Dragon Ball Z. Alternatively: Any of the ‘big three’ manga – Naruto, Bleach or One Piece, all hugely influential to game designers.

Originally serialised in the weekly Japanese comic, Shōnen Jump, Dragon Ball is widely considered to be one of the greatest mangas of all-time, its volumes selling over 230m copies worldwide. Based around the Chinese novel Journey to the West (the source for the cult TV series Monkey), the epic work combines exciting martial arts action and a Picaresque narrative heaving with eccentric and fascinating characters. There have been dozens of video game conversions of the original works, but Toriyama’s mix of combat, mythology and comedy has inspired hundreds more beat-’em-ups and action adventures. There are also dozens of games that make use of the “over 9000” meme, originating from Dragon Ball Z. Alternatively: Any of the ‘big three’ manga – Naruto, Bleach or One Piece, all hugely influential to game designers.

Video games are utterly crammed with conventions, ideas and archetypes ripped from world mythologies, but Ancient Greece has provided many of the key inspirations. The idea of the heroic quest, a central element in almost every role-playing game, is symbolised in the adventures of Odysseus, Perseus and Theseus, as are the underlying concepts of prophesy, destiny and of ‘the chosen one’ who is born to vanquish evil. This inspiration is obvious in titles like God of War and Altered Beast, but every time a character reaches for a magic item or feels as though they are at the mercy of vengeful gods, it is likely the source goes back to Ancient Greece. I have opted for Robert Graves’ much-respected analysis here, but there are plenty of other options, including Bullfinch’s Mythology. Alternatively: the Norse and Celtic mythologies have also been a huge influence on game designers, adding their own slants on iconic concepts such as magical items, warring gods and heroic journeys. There’s also the Bible, of course, which is filled with war, heroism and wrathful deities.

Video games are utterly crammed with conventions, ideas and archetypes ripped from world mythologies, but Ancient Greece has provided many of the key inspirations. The idea of the heroic quest, a central element in almost every role-playing game, is symbolised in the adventures of Odysseus, Perseus and Theseus, as are the underlying concepts of prophesy, destiny and of ‘the chosen one’ who is born to vanquish evil. This inspiration is obvious in titles like God of War and Altered Beast, but every time a character reaches for a magic item or feels as though they are at the mercy of vengeful gods, it is likely the source goes back to Ancient Greece. I have opted for Robert Graves’ much-respected analysis here, but there are plenty of other options, including Bullfinch’s Mythology. Alternatively: the Norse and Celtic mythologies have also been a huge influence on game designers, adding their own slants on iconic concepts such as magical items, warring gods and heroic journeys. There’s also the Bible, of course, which is filled with war, heroism and wrathful deities.

This is a slight cheat as it’s obviously not a novel, but Joseph Campbell’s exhaustive study of world mythologies and the concept of the heroic archetype has been named as an inspiration by countless developers I have spoken to over the last two decades. Campbell’s central argument, that all mythological tales spring from a single monomyth in which a hero defeats a series of challenges to attain a life-changing gift, is central to both video game and movie structure. This is the core stuff of story-telling, later refined into a writing guide by Christopher Vogler in his similarly much-cited work, The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers. Alternatively: Sir James George Frazer’s classic study of archetypal religious beliefs and practices, The Golden Bough, is another oft-named source for video game ideas.

This is a slight cheat as it’s obviously not a novel, but Joseph Campbell’s exhaustive study of world mythologies and the concept of the heroic archetype has been named as an inspiration by countless developers I have spoken to over the last two decades. Campbell’s central argument, that all mythological tales spring from a single monomyth in which a hero defeats a series of challenges to attain a life-changing gift, is central to both video game and movie structure. This is the core stuff of story-telling, later refined into a writing guide by Christopher Vogler in his similarly much-cited work, The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers. Alternatively: Sir James George Frazer’s classic study of archetypal religious beliefs and practices, The Golden Bough, is another oft-named source for video game ideas.

There was a time in the early 2000s when it seemed every studio I visited had a well-thumbed copy of this challenging but fascinating novel left on a desk somewhere. Here, though, it’s as much about form as it is about content – House of Leaves is a cybertext, a work of “ergodic” literature in which the formatting of the text becomes a puzzle the reader must solve. Through footnotes, blank pages, interviews and codes, Danielewski creates a sort of dynamic experience, that reflected a lot of the experiments into interactive fiction and alternative reality gaming taking place on the web at the time. In essence its a story about how to tell stories in the digital age. Alternatively: Fictions by Jorge Luis Borges is another surreal and playful text that creates meaning in obtuse layers – it has been name-checked by many developers I’ve spoken to. A couple also mentioned Theodore Roszak’s Flicker, a slightly more conventional take on Danielewski’s use of fictionalised historical writing.

There was a time in the early 2000s when it seemed every studio I visited had a well-thumbed copy of this challenging but fascinating novel left on a desk somewhere. Here, though, it’s as much about form as it is about content – House of Leaves is a cybertext, a work of “ergodic” literature in which the formatting of the text becomes a puzzle the reader must solve. Through footnotes, blank pages, interviews and codes, Danielewski creates a sort of dynamic experience, that reflected a lot of the experiments into interactive fiction and alternative reality gaming taking place on the web at the time. In essence its a story about how to tell stories in the digital age. Alternatively: Fictions by Jorge Luis Borges is another surreal and playful text that creates meaning in obtuse layers – it has been name-checked by many developers I’ve spoken to. A couple also mentioned Theodore Roszak’s Flicker, a slightly more conventional take on Danielewski’s use of fictionalised historical writing.

Published in 1885, Haggard’s colonialist romp through the deserts and mountains of Africa, brought us Allan Quartermain, the archetypal flawed adventure hero, and introduced the Lost World genre of fiction. These elements, modernised through the Indiana Jones trilogy (don’t… just don’t mention the fourth film), has gone on to inspire everything from Pitfall to Tomb Raider. Any game in which a hero and his bickering team locate a lost temple filled with fabled treasures probably has its roots in Haggard’s novel. Alternatively: Along with Robert Louis Stevenson (Treasure Island) and Edgar Rice Burroughs (Tarzan), Haggard no doubt influenced the heroic fantasy works of authors like Robert E. Howard, whose Conan books have spawned a hundred monosyllabic video game warriors as well shaping the whole sword and sorcery sub-genre.

Published in 1885, Haggard’s colonialist romp through the deserts and mountains of Africa, brought us Allan Quartermain, the archetypal flawed adventure hero, and introduced the Lost World genre of fiction. These elements, modernised through the Indiana Jones trilogy (don’t… just don’t mention the fourth film), has gone on to inspire everything from Pitfall to Tomb Raider. Any game in which a hero and his bickering team locate a lost temple filled with fabled treasures probably has its roots in Haggard’s novel. Alternatively: Along with Robert Louis Stevenson (Treasure Island) and Edgar Rice Burroughs (Tarzan), Haggard no doubt influenced the heroic fantasy works of authors like Robert E. Howard, whose Conan books have spawned a hundred monosyllabic video game warriors as well shaping the whole sword and sorcery sub-genre.

Well, it had to be in here. Although Dungeons and Dragons co-creator Gary Gygax claimed not to have been a fan of Tolkien’s sprawling masterpiece, he conceded its huge influence on his legendary tabletop RPG, specially in the fantastical races that inhabited the rule set. And through D&D, the trilogy has exerted its influence on just about every fantasy video game ever created, from the earliest straight D&D and AD&D conversions to the formative Japanese role-playing games such as Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy, and on into the massively multiplayer era of World of Warcraft. Informed by mythology and folklore, Tolkien established a vast all-encompassing reality to Middle Earth, including a far-reaching sense of history. Arguably, it is Tolkien who taught fantasy game designers about the importance of mythological backstory, of establishing aeons of conflict and lore, lending authenticity to entirely imagined worlds. If a game narrative begins, “after 3,000 years of war…” you can probably blame this guy. Alternatively: Michael Moorcock again, as well as the more playful and parodic Terry Pratchett who subverts all of those supernatural systems for comic effect. And of course, there is a new generation of designers who will grow up on the likes of Brandon Sanderson and Steven Erikson. Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books should not be overlooked either.

Well, it had to be in here. Although Dungeons and Dragons co-creator Gary Gygax claimed not to have been a fan of Tolkien’s sprawling masterpiece, he conceded its huge influence on his legendary tabletop RPG, specially in the fantastical races that inhabited the rule set. And through D&D, the trilogy has exerted its influence on just about every fantasy video game ever created, from the earliest straight D&D and AD&D conversions to the formative Japanese role-playing games such as Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy, and on into the massively multiplayer era of World of Warcraft. Informed by mythology and folklore, Tolkien established a vast all-encompassing reality to Middle Earth, including a far-reaching sense of history. Arguably, it is Tolkien who taught fantasy game designers about the importance of mythological backstory, of establishing aeons of conflict and lore, lending authenticity to entirely imagined worlds. If a game narrative begins, “after 3,000 years of war…” you can probably blame this guy. Alternatively: Michael Moorcock again, as well as the more playful and parodic Terry Pratchett who subverts all of those supernatural systems for comic effect. And of course, there is a new generation of designers who will grow up on the likes of Brandon Sanderson and Steven Erikson. Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books should not be overlooked either.

Certainly not the first cyberpunk novel, but possibly the most influential. Gibson’s post-modern tale of hackers, criminal corporations and sentient AIs worked alongside Bladerunner to instil in game designers a new aesthetic of the future. No shiny spaceships and helpful robots, just noirish paranoia, busted up computer hardware, hard-drinking renegades and drugs. The anarchic, counter-culture feel of Gibson’s works appealed to the bedroom programmers of the 80s and early 90s who identified with the author’s damaged, technically brilliant protagonists, and with the assimilation of biological and computer organisms. Games like Syndicate, Beneath as Steel Sky and later Deus Ex, .hack// and Metal Gear Solid caught the vibe perfectly. Alternatively: pretty much anything by Bruce Sterling, Neal Stephenson or Pat Cadigan. And from manga, Bubblegum Crisis, Ghost in the Shell and Appleseed.

Certainly not the first cyberpunk novel, but possibly the most influential. Gibson’s post-modern tale of hackers, criminal corporations and sentient AIs worked alongside Bladerunner to instil in game designers a new aesthetic of the future. No shiny spaceships and helpful robots, just noirish paranoia, busted up computer hardware, hard-drinking renegades and drugs. The anarchic, counter-culture feel of Gibson’s works appealed to the bedroom programmers of the 80s and early 90s who identified with the author’s damaged, technically brilliant protagonists, and with the assimilation of biological and computer organisms. Games like Syndicate, Beneath as Steel Sky and later Deus Ex, .hack// and Metal Gear Solid caught the vibe perfectly. Alternatively: pretty much anything by Bruce Sterling, Neal Stephenson or Pat Cadigan. And from manga, Bubblegum Crisis, Ghost in the Shell and Appleseed.

Starship Troopers – Robert A. Heinlein

Gears of War, Halo, Killzone, Quake… all of them owe a debt to the concept of the space marine brilliantly realised in Heinlein’s future war epic. He wasn’t the first to write about the concept of a mechanised military defending humanity from invading aliens, but Heinlein captured many of the key elements that would go into the biggest sci-fi games. A troubled hero advancing through the ranks, an insect-like extra-terrestrial threat, a factional military… whatever you think about the archetypal video game space soldier, with his buzz cut, tribal tattoos and immense metallic body armour, it is one of the key images of this console generation, and his family tree goes back to this novel and its contemporaries. Alternatively: Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card, EE Smith’s Lensman series and Iain M Banks’ Culture novels also deal with galactic war, mega weaponry and vicious aliens/AIs. And where would games be without those?

Gears of War, Halo, Killzone, Quake… all of them owe a debt to the concept of the space marine brilliantly realised in Heinlein’s future war epic. He wasn’t the first to write about the concept of a mechanised military defending humanity from invading aliens, but Heinlein captured many of the key elements that would go into the biggest sci-fi games. A troubled hero advancing through the ranks, an insect-like extra-terrestrial threat, a factional military… whatever you think about the archetypal video game space soldier, with his buzz cut, tribal tattoos and immense metallic body armour, it is one of the key images of this console generation, and his family tree goes back to this novel and its contemporaries. Alternatively: Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card, EE Smith’s Lensman series and Iain M Banks’ Culture novels also deal with galactic war, mega weaponry and vicious aliens/AIs. And where would games be without those?

BOXERS and SAINTS. Written and illustrated by Gene Luen Yang. (First Second, $18.99 and $15.99.) In these companion graphic novels, Yang, a Michael L. Printz Award winner, tackles the complicated history of China’s Boxer Rebellion, using characters with opposing perspectives to explore the era’s politics and religion.

ELEANOR & PARK. By Rainbow Rowell. (St. Martin’s Griffin, $18.99.) A misfit girl from an abusive home and a Korean-American boy from a happy one bond over music and comics on the school bus in this novel, which our reviewer, John Green, said “reminded me not just what it’s like to be young and in love with a girl, but also what it’s like to be young and in love with a book.”

FANGIRL. By Rainbow Rowell. (St. Martin’s Griffin, $18.99.) In her second Y.A. novel published in 2013, Rowell cleverly interweaves the story of an introverted girl’s freshman year in college — and first romance — with the “Harry Potter”-like fan fiction she writes in her spare time.

THE 5TH WAVE. By Rick Yancey. (Putnam, $18.99.) Yancey’s wildly entertaining novel, in which aliens come to Earth, manages the elusive trick of appealing to young readers and adults alike.

PICTURE ME GONE. By Meg Rosoff. (Putnam, $17.99.) Mila, a young Londoner with an uncanny gift for empathy, accompanies her father to upstate New York to search for his best friend. Questions of honesty and trust are central to this novel, a National Book Award finalist.

THE RITHMATIST. By Brandon Sanderson. Illustrated by Ben McSweeney. (Tor/Tom Doherty, $17.99.) A boy longs to join a magical cadre defending humanity against merciless “chalklings” in this fantasy, set in an alternate version of America.

ROSE UNDER FIRE. By Elizabeth Wein. (Hyperion, $17.99.) In Wein’s second World War II adventure novel — the first, “Code Name Verity,” was highly praised last year — Rose, 18, an American transport pilot and aspiring poet, struggles to survive in a women’s concentration camp after her plane is grounded in Germany.

◆◆◆

MIDDLE GRADE

BETTER NATE THAN EVER. By Tim Federle. (Simon & Schuster, $16.99.) A 13-year-old escapes to New York for a Broadway audition in this debut novel, described by Patrick Healy in The New York Times as “a twinkling adventure tale for the musical theater set.”

THE CATS OF TANGLEWOOD FOREST. By Charles de Lint. Illustrated by Charles Vess. (Little, Brown, $17.99.) A young girl whose life is saved when magical cats transform her into a kitten learns there are consequences to playing with time and fate.

FLORA AND ULYSSES: The Illuminated Adventures. By Kate DiCamillo. Illustrated by K. G. Campbell. (Candlewick, $17.99.) A freak accident with a vacuum cleaner turns an ordinary squirrel into a superhero in this madcap chapter book by the author of “Because of Winn-Dixie” and “The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane.”

HERO ON A BICYCLE. By Shirley Hughes. (Candlewick, $15.99.) In this first novel by the award-winning picture-book author and illustrator, a family in Nazi-occupied Florence aids the partisans.

MY HAPPY LIFE. By Rose Lagercrantz. Illustrated by Eva Eriksson. (Gecko, $16.95.) In her review on NYTimes.com, Pamela Paul described this chapter book, about a kindergartner’s experience of starting school, as “one of those joyous rarities: a book about girls who are neither infallible nor pratfall-prone, but who are instead very real.”

THE TRUE BLUE SCOUTS OF SUGAR MAN SWAMP. By Kathi Appelt. (Atheneum, $16.99.) In a swamp near the Gulf of Mexico, raccoon brothers search for the yeti-like Sugar Man, who, if awakened, can help save their home from becoming a theme park. Our reviewer, Lisa Von Drasek, said Appelt’s “mastery of pacing and tone makes for wonderful reading aloud.”

◆◆◆

PICTURE BOOKS

AFRICA IS MY HOME: A Child of the Amistad. By Monica Edinger. Illustrated by Robert Byrd. (Candlewick, $17.99.) A West African girl, on board the Amistad when older slaves take over the ship, has a long journey back to her homeland.

THE BEAR’S SONG. Written and illustrated by Benjamin Chaud. (Chronicle, $17.99.) A bear cub chases a bee into the Paris opera house while his father struggles to find him amid the amusing distractions of Chaud’s busy scenes.

BLUEBIRD. Written and illustrated by Bob Staake. (Schwartz & Wade, $17.99.) In this wordless tale of a bullied boy and the bird who helps him, Staake, creator of “The Red Lemon,” has drawn a book of true beauty with a bittersweet ending.

THE BOY WHO LOVED MATH: The Improbable Life of Paul Erdos. By Deborah Heiligman. Illustrated by LeUyen Pham. (Roaring Brook, $17.99.) A picture-book biography of Erdos, the eccentric Hungarian-born mathematician.

BUILDING OUR HOUSE. Written and illustrated by Jonathan Bean. (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $17.99.) A true tale of homesteader parents in the 1970s.

THE DARK. By Lemony Snicket. Illustrated by Jon Klassen. (Little, Brown, $16.99.) A little boy and the darkness he fears reach a detente in this just-spooky-enough story, a New York Times Best Illustrated award winner.

FOG ISLAND. Written and illustrated by Tomi Ungerer. (Phaidon, $16.95.) In this Times Best Illustrated award winner, storm-tossed siblings wash ashore on a forbidden island off the coast of Ireland.

HILDA AND THE BIRD PARADE. Written and illustrated by Luke Pearson. (Flying Eye/NoBrow, $24.) In this graphic novel, a blue-haired girl named Hilda feels out of place in urban Tolberg, until an amnesiac raven helps her settle in.

JOURNEY. Written and illustrated by Aaron Becker. (Candlewick, $15.99.) A lonely girl draws a red door on her bedroom wall and enters a lushly detailed imaginary world.

MR. WUFFLES! Written and illustrated by David Wiesner. (Clarion, $17.99.) A house cat does battle with space aliens in this wordless picture book by Wiesner, a winner of three Caldecott Medals.

SOMETHING BIG. By Sylvie Neeman. Illustrated by Ingrid Godon. (Enchanted Lion, $16.95.) A little boy, frustrated by his desire to do something significant, and his father, who wants to help him, find a new perspective at the seashore.

THIS IS THE ROPE: A Story From the Great Migration. By Jacqueline Woodson. Illustrated by James Ransome. (Nancy Paulsen/Penguin, $16.99.) The multiple Newbery Honor winner Woodson uses a common household item to reflect one family’s experience of the Great Migration.

Entry for the 2014 FOBISIA Short Story Writing Competition with the theme of ‘Magic?’ is now open.

Once again there are 2 divisions, running in the same format as previous years.

Primary (Year 3-6) 600 word limit

Secondary (open) 1000 word limit

Shrewsbury International School Senior entries are due on March 21st.

See your teacher for details.

See this Blog’s posts on last year winners. You can also download the 2010 and 2011 Ebook.

30 Tips for Short Story Writing

For further information see this short video http://video.openroadmedia.com/b7ai/authors-on-writing-short-stories/